Kumano Kodo — Hiking Japan’s Sacred Kumano Sanzan Shrines

The Kumano Kodo, a World Heritage pilgrimage route, refers to five ancient paths that converge on the sacred Kumano region. Matsumoto-toge Pass, which I previously walked, is part of one of these trails — the Iseji route. All routes lead to the Kumano Sanzan: three grand shrines—Kumano Hongu Taisha, Kumano Hayatama Taisha, and Kumano Nachi Taisha—and one temple, Seiganto-ji.

For over a millennium, everyone from retired emperors to samurai and commoners made the demanding journey, spending days crossing steep mountain paths to reach these holy sites. Why did so many endure such hardship to come to Kumano?

Seeking the answer, I headed for the Kumano Sanzan, beginning at Mt. Nachi. There, the vivid red of a three-tiered pagoda stands in perfect contrast to a single silver thread of water plunging down a sheer cliff—an image that lingers long after you’ve seen it.

Previous Articles: Kumano River Boat Tour — Journey Along the Ancient Kawa no Kodo Pilgrimage Route

The approach to Nachi Waterfall begins on Daimonzaka, part of the Kumano Kodo’s Kohechi route. This slope is one of the journey’s most celebrated stretches—its mossy stones and towering cedars preserving the look and feel of the ancient pilgrimage road.

Leaving the paved road, I stepped onto a narrow path beside a weathered stone marker. Before long, a stone torii came into view, followed by a vermilion bridge: Furigase-bashi. In the past, this was the threshold between the everyday world and the sacred mountains. Even nobles who had ridden here on horseback would dismount and walk from this point onward.

After two enormous cedar trees, the trail changes to a stone-paved stairway. In its heyday, nearly a hundred shrines lined this route, and a solitary stone still marks the site of Tafuke-Oji—the last shrine before Nachi Waterfall. Daimonzaka’s 267 steps climb gently over 650 meters, the careful stonework easing the ascent. On either side stand cedars that have been watching over this path for centuries. Beneath their shade, I imagine the pilgrims of old, each step carrying them closer to the roar and mist of the great falls.

After climbing the slope of Daimonzaka, I finally reached the entrance to Mt. Nachi’s sacred approach. The stone steps continued, but from here the path grew livelier with visitors.

At the top of several hundred more steps stood a torii gate, and beyond it, the vivid red halls of Kumano Nachi Taisha. From the shrine grounds, the view stretched out over the deep green folds of Kumano’s mountains. In the precincts, a massive camphor tree stood watch; its hollow trunk forming a passage just wide enough to walk through. Pilgrims still pass beneath it today, carrying votive tablets inscribed with their names and wishes.

To the right of the worship hall lies the main hall of Seiganto-ji Temple. There is no fence or wall to mark where the shrine ends, and the temple begins. Here, Shinto and Buddhism—so different in origin—have mingled for centuries, shaping a unique form of worship that survives strongly in Kumano.

Shinto, Japan’s native tradition, and Buddhism, introduced from abroad, differ at their core, yet here they have long coexisted—shaping and influencing each other until their practices blended seamlessly. Nowhere is this fusion more tangible than in Kumano. From Seiganto-ji’s main hall—one of the oldest structures in the region—the path opens suddenly to an unforgettable view: far ahead, a silver column of water drops in a single, unbroken line from a cliff, while in the foreground the vivid vermilion of a three-tiered pagoda catches the eye. After a moment to take it in, I passed beside the pagoda and began the long stone descent toward the waterfall’s base.

For centuries, Nachi Waterfall has been worshipped as the sacred object of Hirou Shrine, an auxiliary shrine of Kumano Nachi Taisha. From afar, you can already hear its voice, but at the basin, the roar becomes overwhelming. At 133 meters, it is Japan’s tallest single-drop waterfall, and up close its force feels almost divine. It’s easy to see why it has been venerated since ancient times and why pilgrims once journeyed great distances to stand here.

A sheer cliff rising from a deep green forest. A silver ribbon of water falling straight down. Offshore, strange rock formations stand like sentinels along the coast. Kumano’s rugged landscapes—often unreachable—once inspired both fear and devotion. Walking in Mt. Nachi today, you can still feel that same reverence, a quiet reminder of how Japanese spirituality was shaped in constant dialogue with the power of the natural world.

After Kumano Nachi Taisha, I made my way to Kumano Hongu Taisha and Kumano Hayatama Taisha as well—an unmissable chance to better understand the spiritual world woven together by the three shrines of the Kumano Sanzan.

Kumano Hayatama Taisha sits in Shingu City, Wakayama Prefecture, near the border with Mie. It’s about a 30-minute drive from Kumano Nachi Taisha. Passing through the shrine gate, five halls dedicated to the gods of Kumano stretch in a single line, their bright vermilion paint dazzling in the sunlight. A kilometer away lies Kamikura Shrine, said to have originally served as Hayatama Taisha’s main shrine. To reach it, visitors climb 538 steps up an extraordinarily steep stairway, arriving at Gotobiki–iwa Rock—a massive boulder enshrined as the sacred place where the gods of Kumano are said to have first descended.

From Kumano Nachi Taisha, the journey to Kumano Hongu Taisha follows the Kumano River upstream by car for about 40 minutes. Historically, travelers could also take the river route downstream from Hongu to Kumano Hayatama Taisha, as I noted in another article. Kumano Hongu Taisha is the head shrine of over 3,000 Kumano shrines nationwide. Among the Kumano Sanzan, it exudes the most ancient and traditional atmosphere, with its calm, understated shrine buildings forming a striking contrast to the vivid vermilion of Hayatama Taisha. Just nearby lies Oyunohara, a sacred site where the main shrine once stood until it was destroyed by a massive flood in the late 19th century. Beyond fields of ripening rice, a massive torii—said to be Japan’s tallest—rises with an awe-inspiring presence.

Walking the Kumano Kodo and visiting the Kumano Sanzan is more than a scenic journey—it is a walk, through centuries of Japanese spirituality, shaped by untamed nature. Along moss-covered paths, past towering cedars, and over stone steps, the footsteps of pilgrims past still echo. From the vivid halls of Kumano Nachi Taisha to the serene sanctuaries of Kumano Hongu Taisha, each site tells a story of devotion and reverence. The roaring Nachi Waterfall, sacred Gotobiki-iwa Rock, and massive torii at Oyunohara remind travelers of the enduring power of faith and why generations have returned to feel the divine presence in Kumano’s mountains, rivers, and forests.

As the pilgrimage ends, the journey naturally leads to another mountain sanctuary: Mt. Koya. Founded by Kobo Daishi, it represents a different chapter in Japan’s spiritual heritage yet shares the same sense of awe inspired by sacred landscapes. Traveling from the Kumano Sanzan to Mt. Koya, one witnesses a continuity of faith that has shaped Japan’s mountains, rivers, and forests for over a thousand years. This is a journey not just across geography, but through history, devotion, and the enduring dialogue between humans and nature.

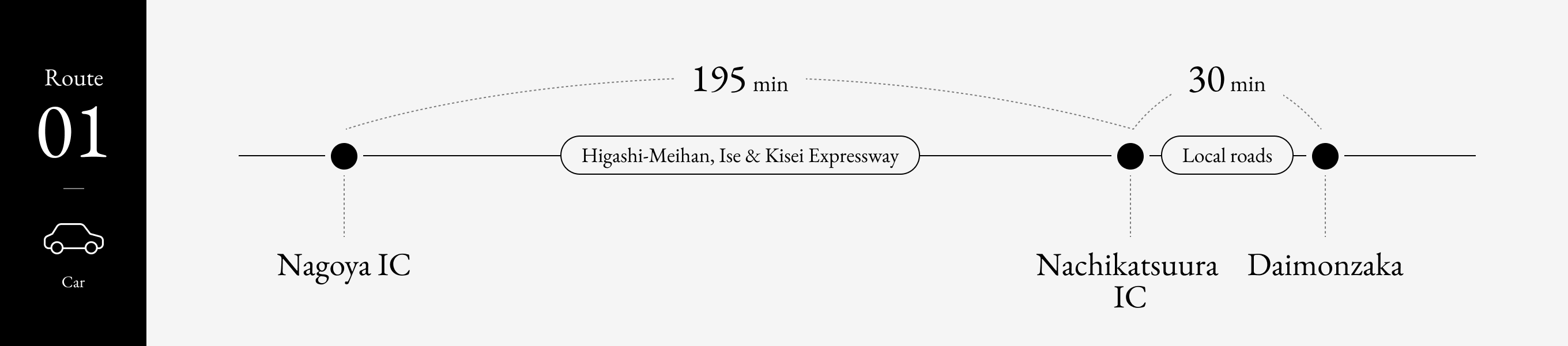

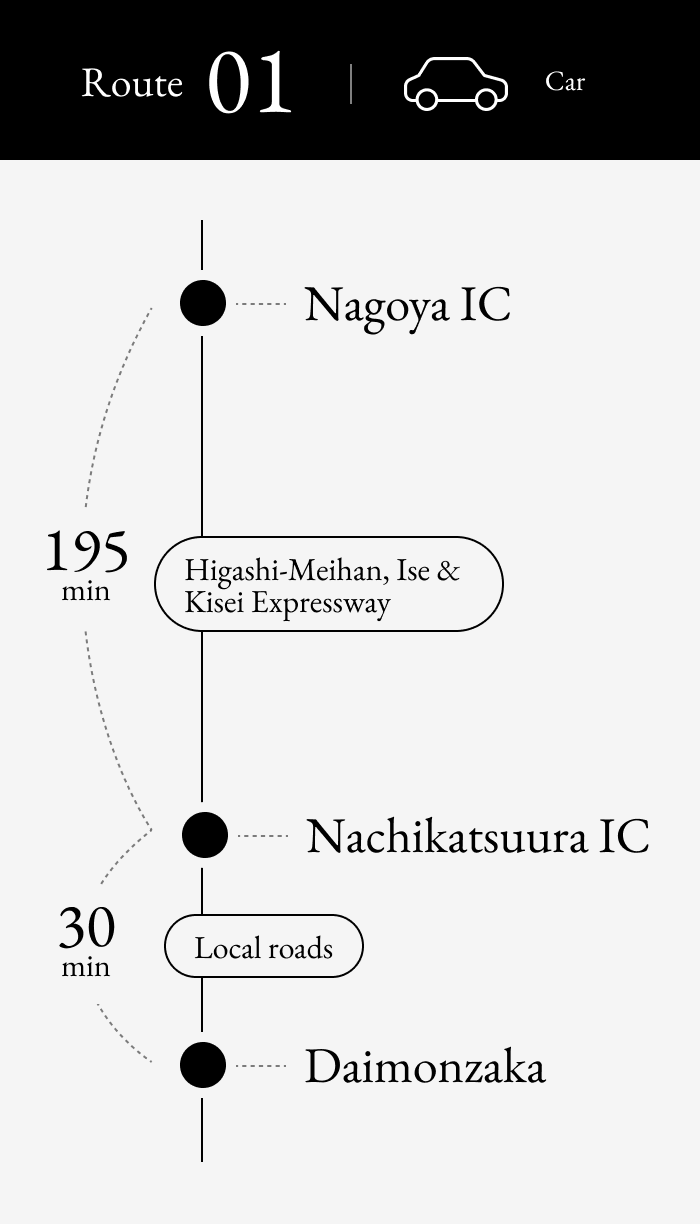

It takes about 3 hours 15 minutes to drive from Nagoya IC to Nachikatsuura IC via the Higashi-Meihan Expressway, Ise Expressway, and Kisei Expressway. After exiting at Nachikatsuura IC, continue on local roads toward Nachi Falls and follow signs to Daimonzaka parking area, which takes approximately 30 minutes. The route leads through the mountainous Kumano region.

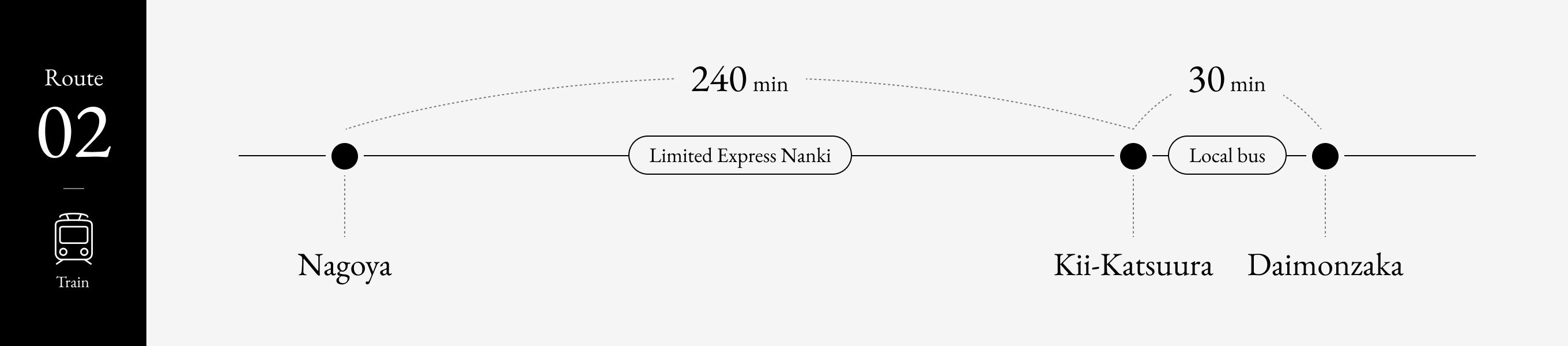

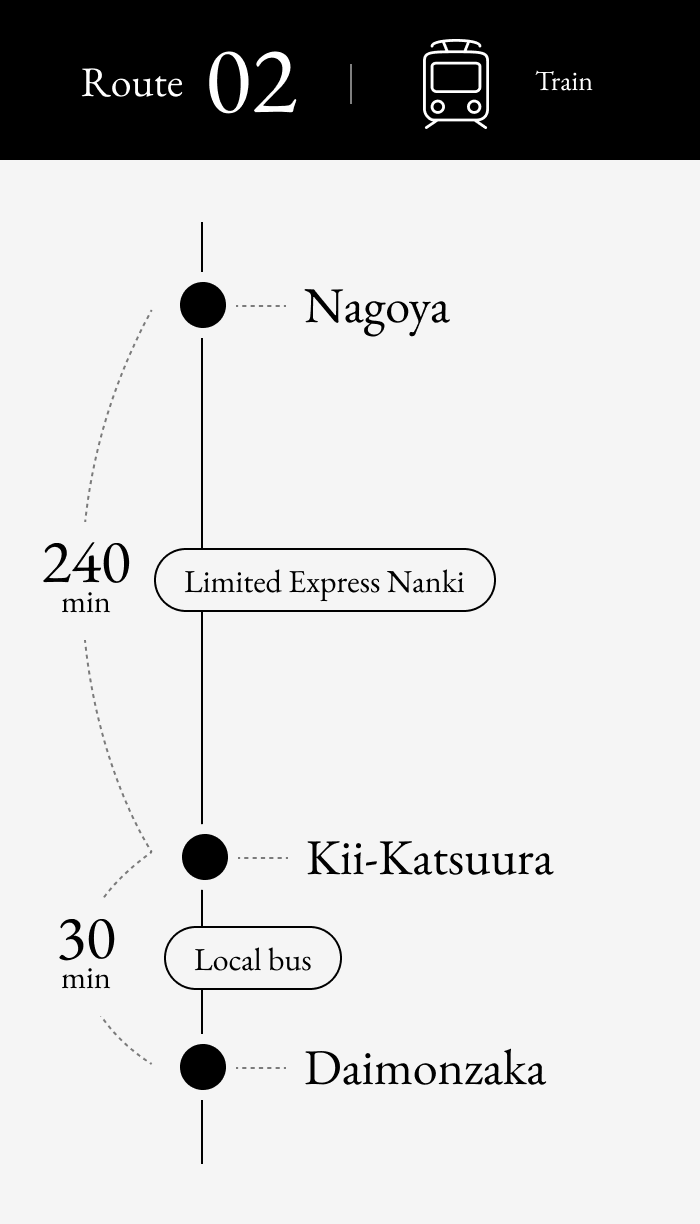

By public transportation, take the JR Limited Express Nanki from Nagoya Station to Kii-Katsuura Station (about 4 hours). From Kii-Katsuura Station, take a Kumano Kotsu bus bound for Nachi-san and get off at Daimonzaka bus stop (about 30 minutes). The bus stop is located at the entrance to this famous stone-paved section of the Kumano Kodo pilgrimage trail. The total journey time is approximately 5 hours including transfer time.