Wada-toge Pass to Shimosuwa-juku — Hiking the Nakasendo’s Most Challenging Stretch

The stretch of the Nakasendo between Shimosuwa-juku—the 29th post town from Edo, modern-day Tokyo—and Wada-juku spans around 23 kilometers, making it by far the longest section of the route. Unlike the usual 8-kilometer segments, this stretch includes a steep climb over Wada-toge Pass, the highest and most treacherous point on the entire Nakasendo. Rising to approximately 1,600 meters, the pass posed a serious challenge for travelers of the Edo period (1603–1868), who braved the route every season—even through deep snow in winter.

Both Shimosuwa-juku and Wada-juku sit at around 800 meters above sea level, meaning travelers faced a grueling 800-meter ascent. In the colder months, the climb became even more punishing, as snow transformed the trail into a deadly trial. It is no surprise, then, that Wada-juku thrived as a rest stop at the foot of the climb. Nearly every traveler from Edo paused here to recover and prepare for the difficult journey ahead.

On the other side, Shimosuwa-juku welcomed the weary with its famous hot springs—making it the only onsen town on the entire Nakasendo. Even today, its soothing baths continue to draw visitors looking to unwind after exploring the historic route. As we saw in Narai-juku, it is no coincidence that important post towns were located near dangerous mountain passes. Travelers from Edo would always stop at Wada-juku, situated at the foot of the steep Wada-toge Pass, to rest and regain their strength before the climb.

Up to this point, we have been walking the Nakasendo from Kyoto toward Edo. This time, however, we will go in the opposite direction—from Wada-juku to Shimosuwa-juku—for a smoother hike. Part of the trail is on a real road, and while it is possible to complete the full route in a day, Route 142 is a busy road with no sidewalks, making it unsuitable for walking. So instead, we drove to the start of the hiking trail. Although the trail itself is well maintained and easy to follow, the trailhead can be hard to find, especially for first-time visitors. We strongly recommend going with a knowledgeable local guide. Yes, the trail is long, steep, and even hard to reach—but this is where the true Nakasendo lives. And that alone makes it worth the effort.

Before hitting the trail, we took a moment to explore Wada-juku—an Edo-period post town established in 1602 when the Nakasendo was formalized for official travel under the Sankin-kotai system. Sankin-kotai was a system that required feudal lords to travel regularly to Edo, creating grand processions that could be a financial burden on some. The challenging 23-kilometer path to Shimosuwa-juku was completed around 1614. Like other post towns, Wada-juku provided lodging, horses, porters, and rest for travelers on shogunate business. It also played a key role in the shogunate’s official courier network.

Walking through the town today, it is easy to feel its history. Rows of traditional buildings line the old highway, and at the town center stands the honjin—a grand structure once reserved for feudal lords, imperial envoys, and other elite travelers. Large stones weigh down its wooden roof, as if anchoring centuries of tradition. The interior is now open to the public, offering a rare look inside one of the most prestigious buildings on the route. In fact, Wada-juku’s honjin is a remarkable survivor. None of the post towns we have visited so far—Magome-juku, Tsumago-juku, Yabuhara-juku or Narai-juku—have a honjin as intact as this. Its central, well-defended location reflects the standardized town layout seen across the Nakasendo.

Pressed for time, we made the honjin our first stop. Its elegant roof lived up to its reputation, and above it stretched a bright blue sky—an ideal start for our journey across Wada-toge Pass.

Related Articles:

・Magome-juku to Tsumago-juku — Follow the Footsteps of Travelers Past

・Torii-toge Pass to Narai-juku — Hike the Historic Nakasendo

If you are an experienced hiker and want to try walking the entire stretch from Wada-juku to Shimosuwa-juku in a single day—go prepared—steep elevation changes make this the toughest section of the Nakasendo. Add to that the public transport to Wada-juku is limited, and you have a logistical challenge as well. That is why we recommend a smarter approach: take the train from Narai Station to Shimosuwa Station (via Shiojiri), then stay the night in Shimosuwa—your destination for the day. With a smooth transfer, the trip takes about an hour.

From Shimosuwa, go to Wada-juku and head toward Omekura-guchi along Route 142. This is the halfway point to Wada-toge Pass at 1,100 meters. From there, it is an 8-kilometer hike over the pass down to Route 142 near the Shin-Wada Tunnel—about three hours on foot. Unlike Magome-toge or Torii-toge Pass, there is no convenient train station nearby. This is the hardest route to reach so far. But according to veteran Nakasendo guides, “this is the real Nakasendo.”

Why? Because the trail over Wada-toge Pass retains its original Edo-period form. Moss-covered stone paths still trace the same lines walked by travelers and horses centuries ago. And because few people come here, the silence lets you sink fully into the landscape and the past. Just minutes after we began, we stumbled on something unforgettable: a cluster of weathered stone statues glowing in the morning sun. Perhaps they were placed to guard those brave enough to cross this perilous pass.

The climb remains gentle as we continue, accompanied by the soft sound of a nearby stream and the pleasant crunch of fallen leaves underfoot. The trail is wide—spanning two to three meters—and that is no accident. According to our guide, this was part of an official policy during the Edo period. Highways like the Nakasendo were required to be at least one ken wide (about 1.8 meters), wide enough to allow palanquins carrying samurai and officials to pass through. The wide path reflects how it would have looked in the past—more like a historical road than a modern mountain trail.

Over an hour into the hike, I realized I had not passed a single person. Then, I reached a stretch of stone pavement that stopped me in my tracks—not for its beauty, but for its raw authenticity. Unlike the artfully arranged paths of Magome-toge or Torii-toge Pass, these stones were uneven, weathered, and clearly not laid for tourists. Every step felt like it carried a weight you could feel—each mossy slab breathing with the memory of those who passed over it centuries ago. It is a rough path, but an honest one. A fragment of the past, still intact.

Between the trailhead at Omekura-guchi and Wada-juku lies another rare historical feature: a well-preserved ichirizuka, or distance marker mound. These were set at regular intervals—one ri apart (about 3.9 km)—to help travelers measure their journey. If you are a history lover, make time to visit the Karasawa Ichirizuka. It is a humble site, but one more piece of the road’s original spirit.

Getting back to the trail, I walked a gentle but steady incline that continued as the path crossed Route 142, where the occasional car whirs past. Step by step, we approach the summit. At 1,600 meters, Wada-toge Pass is the highest point on the Nakasendo. When I look up, the sky, glimpsed between thick branches, feels closer somehow—like I have entered the final stretch of a mountain climb. There is a quiet thrill as the peak is just within reach.

Then, suddenly, the trees fall away, and a vast sky unfolds before me. Wisps of cloud drift across distant ridgelines—those are the peaks of Mt. Kisokoma, part of the Central Japanese Alps. And there, barely outlined in the haze, is Mt. Ontake again, last seen from Torii-toge Pass. At this height, the scenery is awe-inspiring. I linger for a while, letting the crisp wind brush past as I soak in the panorama.

It has been about two hours since I started climbing. I pause for a simple lunch, grateful for the quiet—no one else is around. I enjoy the view in peace, then, with one last look, I begin the descent. The west side of the pass is much steeper and narrower. Once two meters wide, the trail is now a little more than a footpath in places. I descend steadily, following switchbacks that zigzagged across the slope.

At one bend, I turn around. Behind me, the old highway stretches straight up toward the pass—a remnant of the original Nakasendo from the Edo period. Hauling a heavy load up that grade must have been brutal. When you consider how far it is between Shimosuwa and Wada-juku, you realize people had no choice but to go straight up. For some people used to the comforts of modern life, it is a grueling climb.

As I continued downhill, the trail dropped in elevation quickly and soon brought me into a quiet, stone-lined clearing. The Nakasendo winds through this historic site, and at the bottom of the slope, a sign marked the remains of Nishi Mochiya—the western rice cake shop. Back in the days of sankin kotai, four such rice cake shops stood here, selling their specialty rice cakes to weary travelers.

Along Wada-toge Pass, there were five locations with teahouses and rice cake shops, which provided shelter and rest to travelers braving the steep climb. I had passed the ruins of Higashi Mochiya earlier—the eastern rice cake shop—now little more than a shell, but once a vital rest stop for both people and horses, and a refuge from sudden storms.

Beyond Nishi Mochiya, the Nakasendo keeps going. But this may be the last of the lush mountain scenery. I passed another ichirizuka and followed a clear mountain stream down to where the trail meets National Route 142. From here, there is no choice but to walk alongside the modern road.

There are more historical spots ahead, but as I noted at the beginning, walking this stretch is not recommended due to safety concerns. The area has modernized; Route 142 now cuts straight through the mountains with a massive tunnel, a vital artery for today’s car-driven society. No matter the era, the Wada-toge Pass remains a key route through the mountains.

Follow National Route 142 and you will arrive at Shimosuwa-juku. In 1843, it boasted over 300 households and a population exceeding 1,300. By contrast, Wada-juku, a more modest stop, had just 130 homes and a population of about 500, underscoring Shimosuwa’s significance.

Shimosuwa-juku is the only post town along the Nakasendo with its own hot spring—and it is also home to Harumiya and Akimiya, two of the four shrines of Suwa Taisha, one of Japan’s oldest. This historic junction was where the Koshu Kaido, one of the Five Edo Routes, met the Nakasendo. Travelers paused here before the demanding Wada-toge Pass, mingling with pilgrims and hot spring seekers. It was a true hub of movement and meaning.

The town’s honjin, once reserved for important officials, is known for its exquisite strolling garden—said to be the finest along the Nakasendo and still featuring Edo-period flora. Just steps away stands a stone marker where the two great roads converge. I found myself captivated by the rows of elegant wooden inns, and an enchanting streetscape opened before me. One that continues to charm visitors.

Walking down the street, I arrive at Suwa Taisha Shimosha (Lower Shrines), rooted in ancient tree worship, which commands spiritual reverence. The grand Onbashira Festival, held every six years, sees brave men ride towering logs down steep slopes. Harumiya and Akimiya each guard four sacred trees, and their shrine buildings—crafted by master carpenters—are architectural treasures. Step inside and you are met with a hush of sacred stillness. Centuries ago, travelers would have stopped here to pray for safe passage through the mountains ahead.

Just like travelers in the Edo period, I took my time soaking in Shimosuwa’s hot springs, letting the weariness of crossing multiple mountain passes slowly melt away. Next, the destination is Karuizawa. A dramatic change from the scenic hot spring town, Karuizawa, is now one of Japan’s premier resort areas. Though it has become synonymous with summer retreats today, its origins lie in its past as Karuizawa-juku, a bustling post town on the Nakasendo. Walking the old road, retracing history — what stories will the next leg of this journey reveal? With anticipation held in check, I boarded the train heading to Nagano.

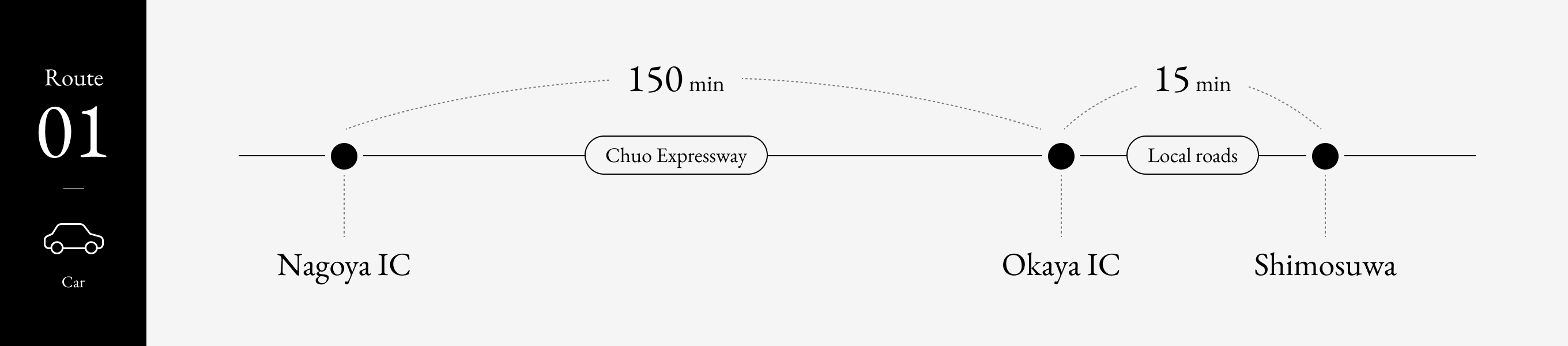

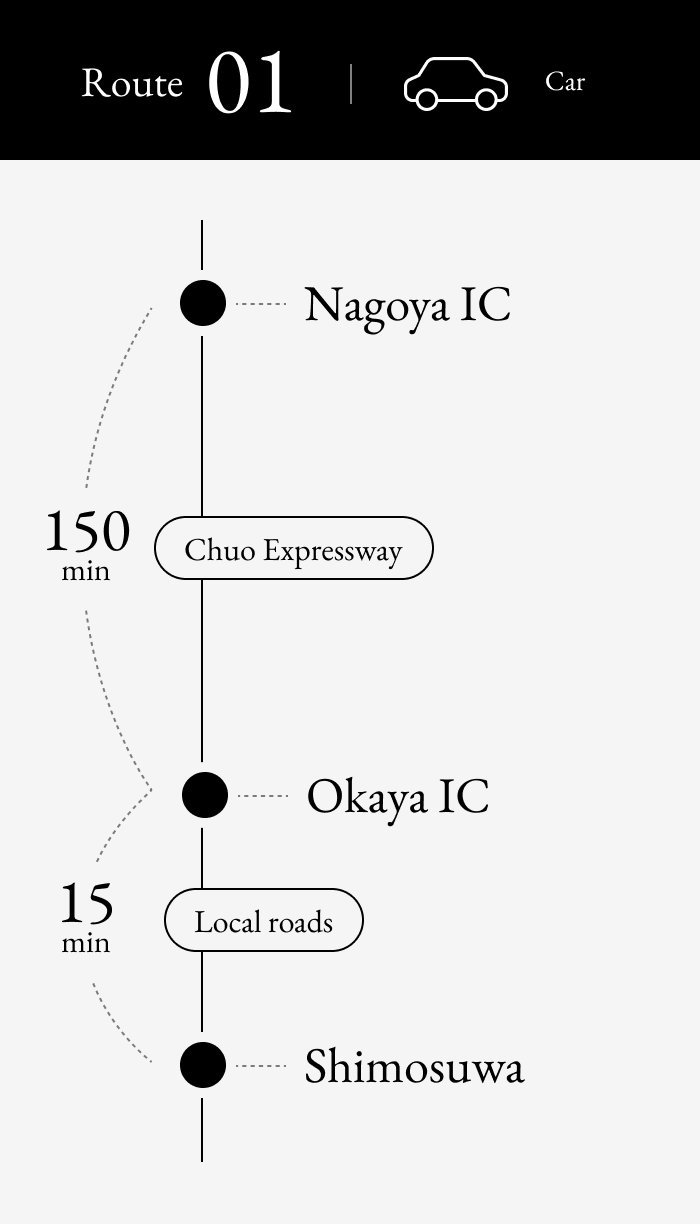

It takes about 2 hours 30 minutes to drive from Nagoya IC to Okaya IC via the Chuo Expressway. After taking the Okaya IC exit, continue on local roads to Shimosuwa, which takes approximately 15 minutes.

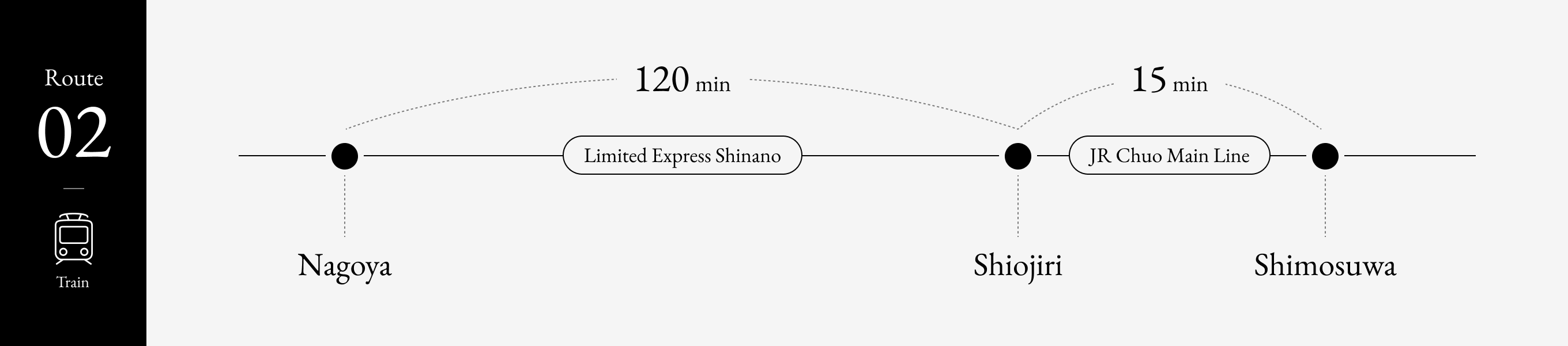

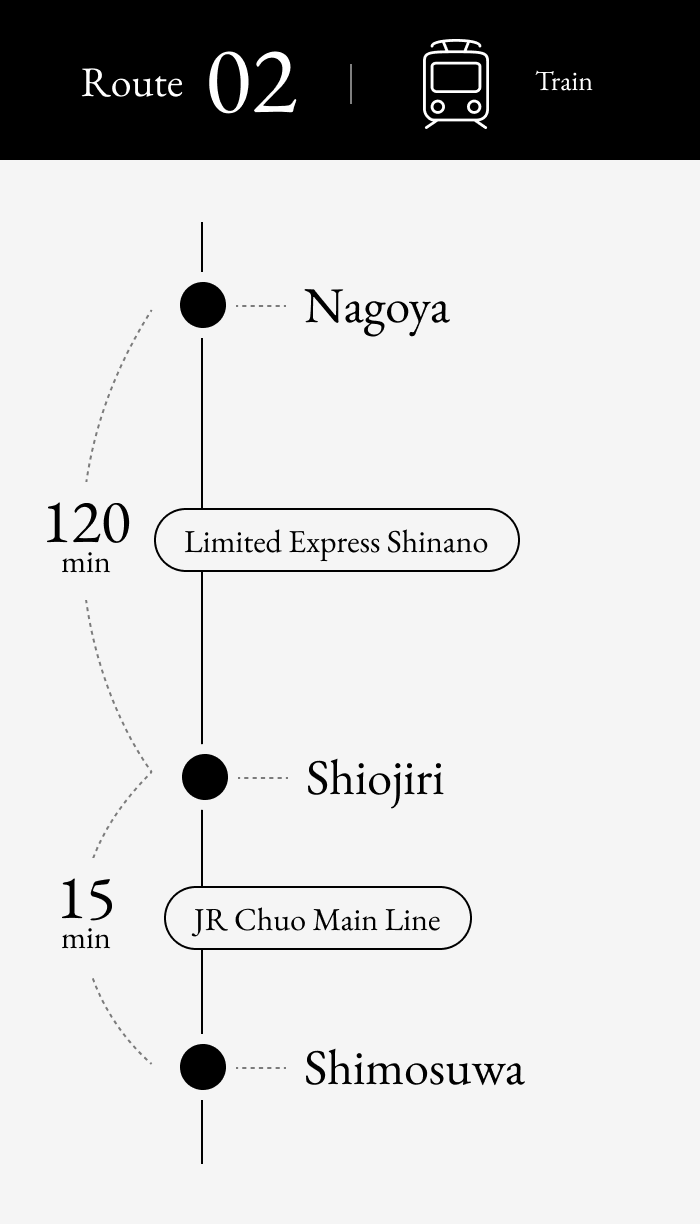

By public transportation, take the Limited Express Shinano from Nagoya Station to Shiojiri Station (about 2 hours). From Shiojiri Station, transfer to a local train on the JR Chuo Main Line bound for Kofu and get off at Shimosuwa Station (about 15 minutes). Shimosuwa Station is located in the center of this historic post town along Lake Suwa. The total journey time is approximately 2 hours 30 minutes including transfer time.

Next Article » Old Karuizawa — The Untold Nakasendo Story