Torii-toge Pass to Narai-juku — Hike the Historic Nakasendo

Stretching for one kilometer, Narai-juku’s row of Edo-period houses (1600s-1800s) stands as one of the Nakasendo’s greatest highlights. Nicknamed Narai of a Thousand Houses, it still lives up to that name today, with unbroken rows of historic buildings preserving its old-world charm. The route crossing Torii-toge Pass, at 1,197 meters, toward Narai-juku is well-maintained for trekking, making it an ideal path for those journeying on foot along the old highway. While the Nakasendo is best known as the highway where samurai lords were required to travel with large entourages to show loyalty and maintain control—this single road weaves together countless moments from many eras. The rich layers of history accumulated over centuries give the path an appeal that goes far beyond an ordinary hike.

Torii-toge Pass, named after the torii gate that gives it its identity, boasts a history stretching back over 1,300 years. A torii still stands near the pass today, rising majestically from the mountains and imbuing the area with a profound sense of sacredness. A torii is a traditional Japanese gate marking the entrance to a Shinto shrine, symbolizing the divide between the sacred realm of the gods and our everyday world. Exploring the legends woven along this highway makes the Samurai Trail even more captivating. Once a sacred pilgrimage route, a vital travel artery, and the stage for fierce battles, Torii-toge Pass invites you to step onto its trail and uncover its many layers of history for yourself.

Previous Article: Magome-juku to Tsumago-juku — Follow the Footsteps of Travelers Past

This day’s trek begins at JR Yabuhara Station in Kiso Village, Nagano Prefecture. From Nagiso Station—the closest stop to Tsumago-juku, where the previous leg ended—it’s an easy one-hour local train ride. While the stretch from Magome-juku to Tsumago-juku is the most popular section of the Nakasendo, the route from Yabuhara-juku—one of the eleven Kiso post towns—across Torii-toge Pass to Narai-juku offers its own unique appeal. Although trains run roughly once an hour, the station’s convenient location makes it easy to start early. When I arrived, hikers with daypacks and sturdy boots were already setting out along the trail. The 6.5-kilometer path takes about three hours at a comfortable pace, though confident hikers can complete it in as little as two hours, arriving at Narai-juku with energy to spare.

Just a few steps in, I found myself in Yabuhara-juku, where traces of the Edo period remain visible. Unlike Tsumago-juku, which preserves an unbroken row of Edo-period houses, Yabuhara-juku reveals an intriguing blend of old and modern streetscapes side by side. Yabuhara-juku is also famous as the birthplace of traditional wooden combs. Known as Oroku-gushi, these special combs are still handmade by craftsmen using minebari, a tough, flexible wood—a craft passed down since the Edo period and still one of the Kiso region’s signature local specialties.

Looking back at the path behind me, I noticed how the road twists at a sharp, almost right angle as it meets the post town—a clever design called a masugata, which I knew from my love of Japanese castles. This feature, often found near the gates of post towns and castles, was built to stop enemies from charging straight in. In other words, post towns were never just overnight stops; they were vital military, political, and logistical hubs that needed to be defended.

After passing through Yabuhara-juku and climbing a gentle slope through the neighborhood, I finally reached the start of the true mountain trail. From a hilltop, the houses fell away behind me, and the old Nakasendo stretched straight ahead, even where modern train tracks cut across its path.

The mountain trail was well maintained, with a bilingual (Japanese and English) course map at the entrance—a good spot to get a clear sense of the route ahead. The main sights I looked forward to were the viewpoint along the climb to the pass, the torii gate that gave Torii-toge Pass its name, a grove of towering horse chestnut trees, and the remains of an old Warring States Period battlefield. From there, the path quickly shifted into true mountain terrain, though the slope stayed gentle enough to keep a steady pace and take in the scenery. When I came in early June, the fresh greenery was just coming alive; everywhere I looked, young leaves and crisp air gave the trail a bright, invigorating feel. The natural path, covered in fallen leaves and thick vegetation, offered excellent cushioning that eased the strain on my knees. For now, I kept moving forward, setting my sights on the viewpoint.

The pass is a mountain trail linking Nagano’s Kiso and Matsumoto regions, and was once famed as one of the toughest challenges on the Nakasendo. Its name carries the weight of history, tied to legends of the warlord Kiso Yoshimoto in the Warring States Period. In the late 15th to early 16th century, Kiso Yoshimoto, lord of Kiso, paused at this very pass before setting out to fight the Ogasawara clan of Matsumoto. Facing distant Mount Ontake to the west, he clasped his hands in prayer and asked the gods for victory. According to legend, Yoshimoto received a divine vision in a dream promising triumph, and he went on to win. It’s said this is why the torii gate was built here. The skies were clear, and I could see the very same view that once greeted Yoshimoto. The trail continued on beyond the horizon, but that view gave me the drive to press on and conquer the pass.

After climbing the winding switchbacks, I pressed on up the slope until the trail suddenly opened into a clearing wrapped in vibrant green. I had reached the viewpoint marked on the sign at the trailhead. From this vantage, it was clear just how much of the land was claimed by forest—a view that spoke to the vast, untamed beauty of the Kiso region. Ridges of mountains layered one after another, endlessly into the horizon, while the space where people made their lives was but a tiny fraction. The valley settlements huddled close together, as if seeking warmth, linked by this very highway, threading life through the mountains. The road crossing the pass to connect villages beyond these peaks might appear slender and fragile against the vast forces of nature, yet its role was vital: a lifeline threading through this rugged land. I stepped back onto the mountain path and set out once more, bound for the pass ahead.

Walking along the trail, historic sites appeared one after another, making the uphill climb feel almost effortless. Mount Ontake, once revered by Kiso Yoshimoto, still held deep spiritual significance and drew countless pilgrims. Nestled in the mountains was a stately worship pavilion, flanked by stone statues and memorials, but on this day, I was disappointed as a delicate layer of clouds cloaked the sky, obscuring the mountain from view. As I moved past that point, a large torii gate appeared, surrounded by trees. Standing beneath it and looking up, I was struck by how commanding it felt—far larger than I’d imagined. Its sheer presence embodied the name Torii-toge Pass, and I found myself utterly captivated. Devotion to Mount Ontake grew during the Edo period, long after Yoshimoto’s time. While the exact story remains unknown, it’s possible he sensed a divine presence here and had this impressive gate built.

After passing the place where the torii stood, a relatively flat forest road continued on. A massive horse chestnut tree draped in moss added a touch of mystery to the quiet woods. Records show this mountain pass was first opened as an official government road back in the 8th century. Here, amid this cluster of ancient horse chestnut trees, the deep passage of time felt most tangible. Just how many years had these trunks stood here, growing so wide and strong? Imagining them rooted in this place, silently watching generations of travelers come and go, stirred a profound, wordless feeling within me.

Before long, I arrived at Torii-toge Pass itself, marked by a signpost showing its 1,197-meter elevation. Beyond this point, the trail eased into a gentle descent. I followed the valley path, where the vibrant green foliage grew thicker all around me. This stream also carries the weight of the pass’s long history. By the late 1500s, central government control in Japan had weakened, and renowned warlords like Oda Nobunaga were vying for dominance across the land. Torii-toge Pass emerged as a critical strategic point, witnessing fierce clashes between the Kiso and Takeda clans. The mountain battles here were brutally intense. At a place known as Homuri-sawa—Burial Ravine—more than 500 warriors are said to have fallen, laid to rest in the very gorge that still bears their name.

As I walked this single mountain pass, crossing paths with countless eras, I felt the true thrill of treading a road etched with history. The end of the excursion was now in sight. After passing along a charming stone-paved path, I let myself descend the gentle slope at a brisk pace until I emerged onto a paved road. Just beyond the pass lay Narai-juku, one of the Nakasendo’s longest and grandest post towns. After the long climb, the sudden sight of houses lined up like a living tapestry took my breath away. Dark brown wooden façades line the street, each fronted with latticework that reflects the charm of traditional Japanese architecture. It was a surreal sensation, as if I had stepped into a city from another time—an experience unlike any other. Stretching for about one kilometer along the Narai River, this post town is the largest of the eleven in the Kiso region. It’s truly astonishing that a townscape so faithful to the Edo period has survived on such a grand scale.

After Tsumago-juku, Narai-juku was designated a nationally important preservation district for traditional buildings. Here, renovated folk houses have been turned into charming inns and cafés where visitors can soak in the ambiance of the Edo period as they relax.

Approaching from Edo (modern-day Tokyo), this post town stood right at the foot of the daunting Torii-toge Pass. Here, weary travelers found lodging to rest and recharge before continuing their voyage. Among the 69 post towns lining the Nakasendo, Narai-juku sat 34th from Edo—almost exactly at the halfway mark. The roughly 500-kilometer trek from Edo to Kyoto took travelers about two weeks on foot or horseback. As a key milestone, this place must have carried deep significance for those on the road. Mid-19th-century records show that Narai-juku boasted 30 to 50 inns and a population of over 1,200—roughly double the size of neighboring Tsumago-juku.

Economic activity didn’t just flourish within the post town—it spread into the surrounding region as well. About 1.5 kilometers north of Narai-juku, Kiso-Hirasawa thrived as a center for Kiso lacquerware production. A 30-minute walk along the Nakasendo brought me to this quiet village, where rows of shops display red and black bowls gleaming with a lustrous shine. Here, artisans transform local wood into exquisite lacquerware using traditional techniques that bring out the beauty of natural materials. Once sought after by travelers, merchants, and locals as both practical goods and souvenirs, this craft has been handed down through generations, and its meticulous artistry continues to elevate each piece into a work of art.

Kiso-Hirasawa is easily accessible by its own train station, just a short ten-minute ride from Narai Station, coming from Yabuhara Station where the hike begins. While today’s fast-paced world means even locals rarely travel this historic path on foot, those who choose to walk it uncover a deeper connection with the landscape—a chance to experience hidden sights, quiet moments, and reflections that simply can’t be found by train or car. This journey invites you to slow down, breathe in the rich history, and feel the enduring spirit of the Nakasendo. Looking ahead, the trail climbs toward Wada-toge Pass, perched at approximately 1,600 meters. As the highest point along the entire Nakasendo, Wada-toge Pass is famed as one of the most challenging sections—standing alongside Torii-toge Pass in its toughness. With each step forward, the path grows steeper, and the questions multiply: What stories lie ahead? What trials will this ancient road present? The adventure continues, promising new challenges and unforgettable experiences just beyond the next ridge.

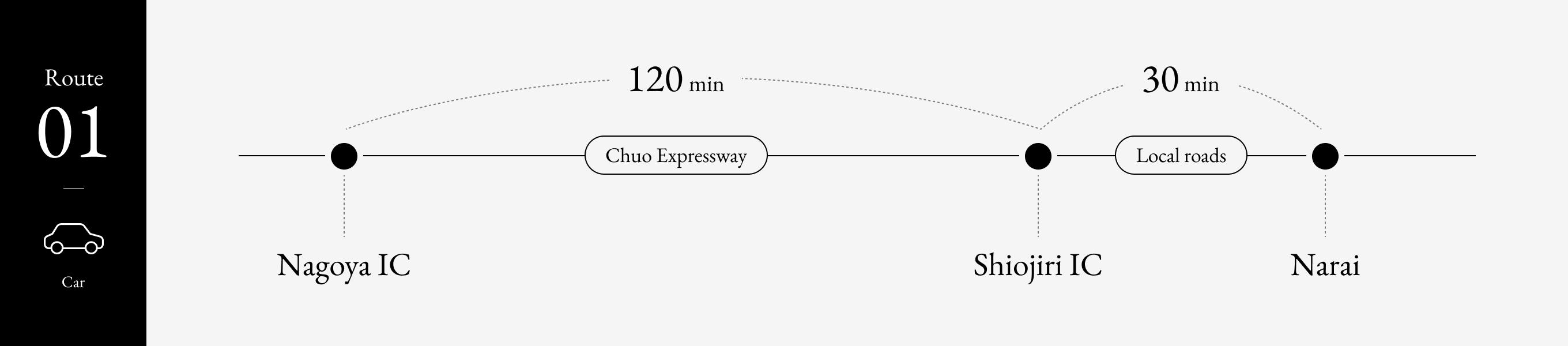

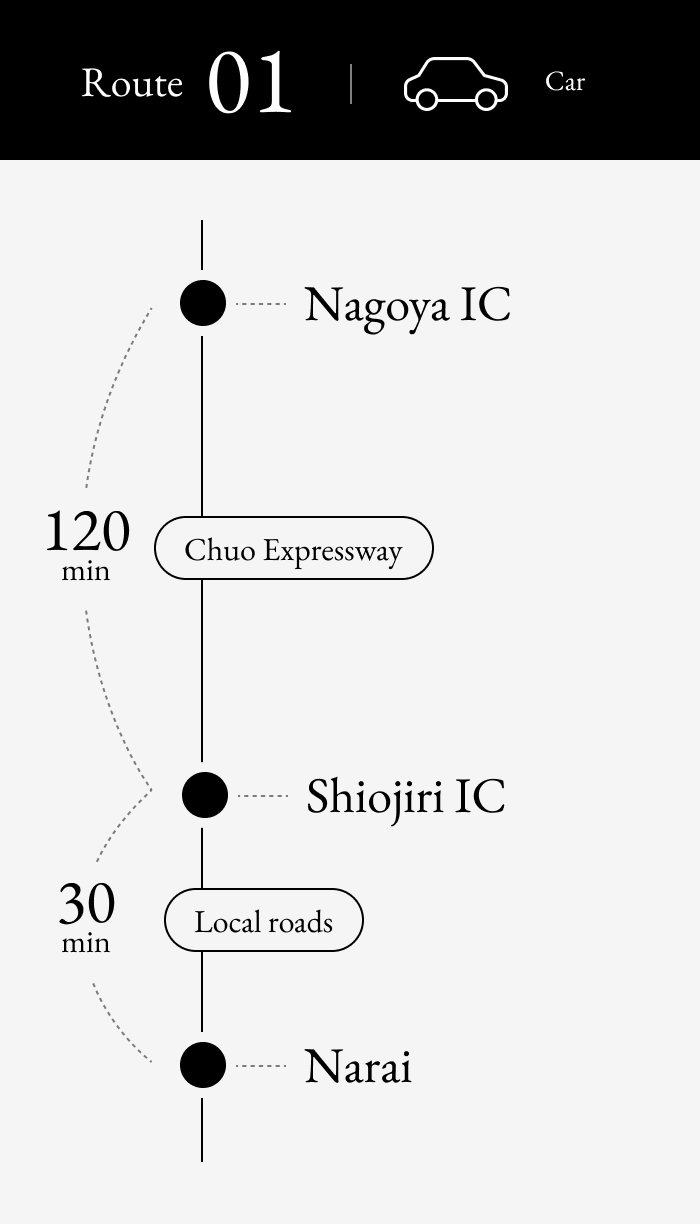

It takes about 2 hours to drive from Nagoya IC to Shiojiri IC via the Chuo Expressway. After exiting at Shiojiri IC, take the local roads to Narai, which takes approximately 30 minutes.

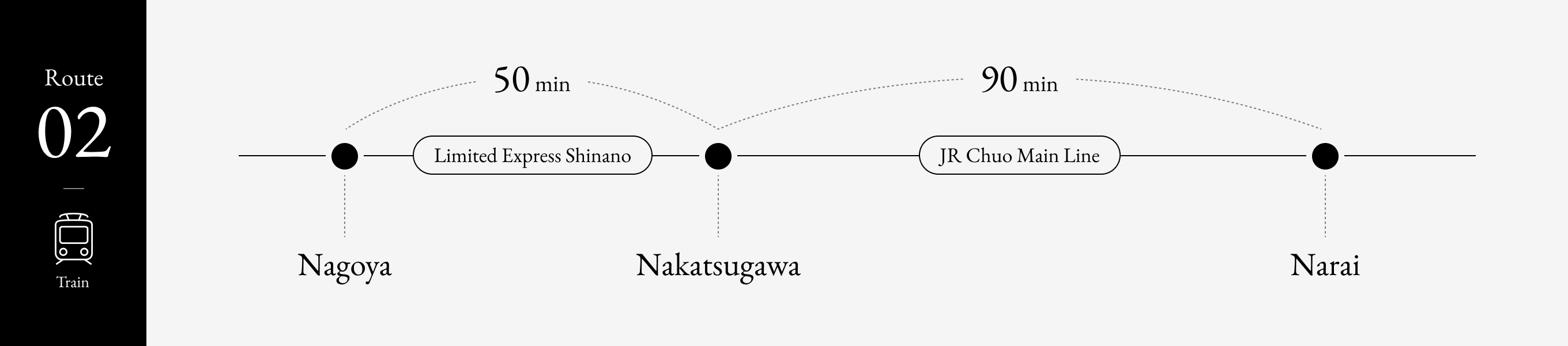

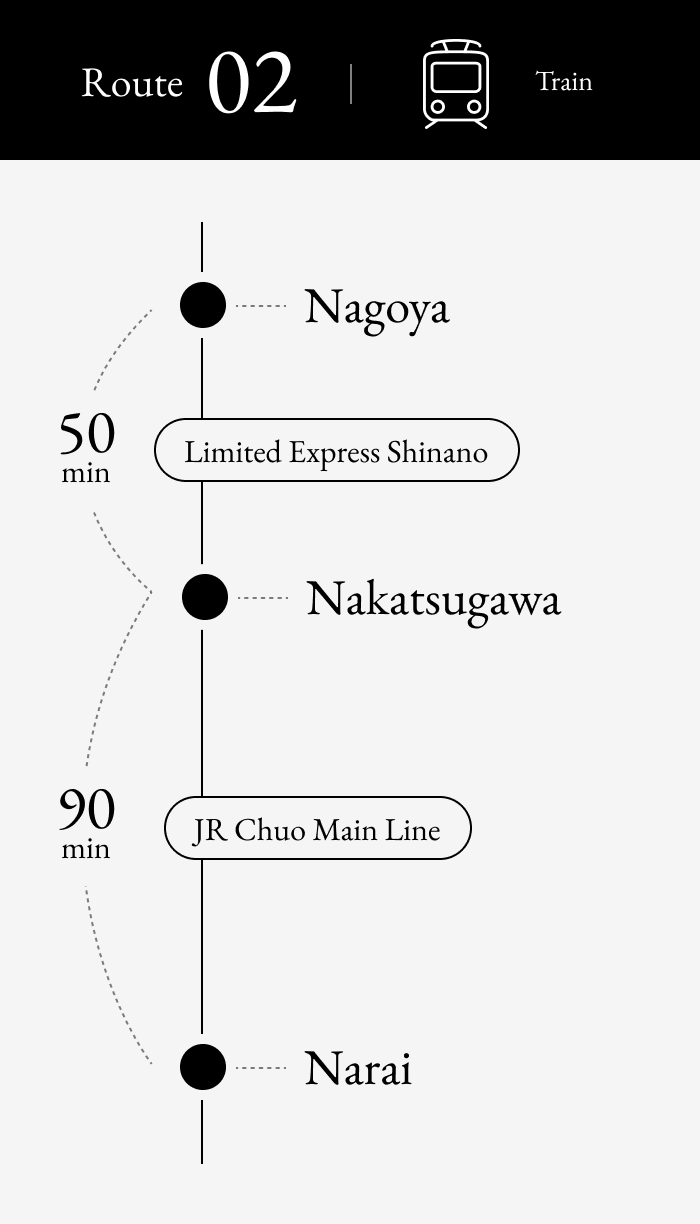

By public transportation, take the Limited Express Shinano from Nagoya Station to Nakatsugawa Station (about 50 minutes). From Nakatsugawa Station, transfer to a local train on the JR Chuo Main Line bound for Matsumoto and get off at Narai Station (about 1 hour 30 minutes). Narai Station is located right in the historic post town, making it very convenient for visitors. The total journey time is approximately 2 hours 30 minutes including transfer time.